| Berenice |

|---|

| MISERY is manifold. |

| The wretchedness of earth is multiform. |

| Overreaching the |

| wide |

| horizon as the rainbow, its hues are as various as the hues of that arch, |

| —as distinct too, |

| yet as intimately blended. |

| Overreaching the wide horizon as the rainbow! |

| How is it |

| that from beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness? |

| —from the covenant of |

| peace a |

| simile of sorrow? |

| But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, |

| out of joy is |

| sorrow born. |

| Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, |

| or the agonies |

| which are have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been. |

| My baptismal name is Egaeus; |

| that of my family I will not mention. |

| Yet there are no |

| towers in the land more time-honored than my gloomy, gray, hereditary halls. |

| Our line |

| has been called a race of visionaries; |

| and in many striking particulars —in the |

| character |

| of the family mansion —in the frescos of the chief saloon —in the tapestries of |

| the |

| dormitories —in the chiselling of some buttresses in the armory —but more |

| especially |

| in the gallery of antique paintings —in the fashion of the library chamber —and, |

| lastly, |

| in the very peculiar nature of the library’s contents, there is more than |

| sufficient |

| evidence to warrant the belief. |

| The recollections of my earliest years are connected with that chamber, |

| and with its |

| volumes —of which latter I will say no more. |

| Here died my mother. |

| Herein was I born. |

| But it is mere idleness to say that I had not lived before |

| —that the |

| soul has no previous existence. |

| You deny it? |

| —let us not argue the matter. |

| Convinced myself, I seek not to convince. |

| There is, however, a remembrance of |

| aerial |

| forms —of spiritual and meaning eyes —of sounds, musical yet sad —a remembrance |

| which will not be excluded; |

| a memory like a shadow, vague, variable, indefinite, |

| unsteady; |

| and like a shadow, too, in the impossibility of my getting rid of it |

| while the |

| sunlight of my reason shall exist. |

| In that chamber was I born. |

| Thus awaking from the long night of what seemed, |

| but was |

| not, nonentity, at once into the very regions of fairy-land —into a palace of |

| imagination |

| —into the wild dominions of monastic thought and erudition —it is not singular |

| that I |

| gazed around me with a startled and ardent eye —that I loitered away my boyhood |

| in |

| books, and dissipated my youth in reverie; |

| but it is singular that as years |

| rolled away, |

| and the noon of manhood found me still in the mansion of my fathers —it is |

| wonderful |

| what stagnation there fell upon the springs of my life —wonderful how total an |

| inversion took place in the character of my commonest thought. |

| The realities of |

| the |

| world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the |

| land of |

| dreams became, in turn, —not the material of my every-day existence-but in very |

| deed |

| that existence utterly and solely in itself. |

| - |

| Berenice and I were cousins, and we grew up together in my paternal halls. |

| Yet differently we grew —I ill of health, and buried in gloom —she agile, |

| graceful, and |

| overflowing with energy; |

| hers the ramble on the hill-side —mine the studies of |

| the |

| cloister —I living within my own heart, and addicted body and soul to the most |

| intense |

| and painful meditation —she roaming carelessly through life with no thought of |

| the |

| shadows in her path, or the silent flight of the ravenwinged hours. |

| Berenice! |

| —I call |

| upon her name —Berenice! |

| —and from the gray ruins of memory a thousand |

| tumultuous recollections are startled at the sound! |

| Ah! |

| vividly is her image |

| before me |

| now, as in the early days of her lightheartedness and joy! |

| Oh! |

| gorgeous yet |

| fantastic |

| beauty! |

| Oh! |

| sylph amid the shrubberies of Arnheim! |

| —Oh! |

| Naiad among its |

| fountains! |

| —and then —then all is mystery and terror, and a tale which should not be told. |

| Disease —a fatal disease —fell like the simoom upon her frame, and, even while I |

| gazed upon her, the spirit of change swept, over her, pervading her mind, |

| her habits, |

| and her character, and, in a manner the most subtle and terrible, |

| disturbing even the |

| identity of her person! |

| Alas! |

| the destroyer came and went, and the victim |

| —where was |

| she, I knew her not —or knew her no longer as Berenice. |

| Among the numerous train of maladies superinduced by that fatal and primary one |

| which effected a revolution of so horrible a kind in the moral and physical |

| being of my |

| cousin, may be mentioned as the most distressing and obstinate in its nature, |

| a species |

| of epilepsy not unfrequently terminating in trance itself —trance very nearly |

| resembling positive dissolution, and from which her manner of recovery was in |

| most |

| instances, startlingly abrupt. |

| In the mean time my own disease —for I have been |

| told |

| that I should call it by no other appelation —my own disease, then, |

| grew rapidly upon |

| me, and assumed finally a monomaniac character of a novel and extraordinary |

| form — |

| hourly and momently gaining vigor —and at length obtaining over me the most |

| incomprehensible ascendancy. |

| This monomania, if I must so term it, consisted in a morbid irritability of |

| those |

| properties of the mind in metaphysical science termed the attentive. |

| It is more than |

| probable that I am not understood; |

| but I fear, indeed, that it is in no manner |

| possible to |

| convey to the mind of the merely general reader, an adequate idea of that |

| nervous |

| intensity of interest with which, in my case, the powers of meditation (not to |

| speak |

| technically) busied and buried themselves, in the contemplation of even the most |

| ordinary objects of the universe. |

| To muse for long unwearied hours with my attention riveted to some frivolous |

| device |

| on the margin, or in the topography of a book; |

| to become absorbed for the |

| better part of |

| a summer’s day, in a quaint shadow falling aslant upon the tapestry, |

| or upon the door; |

| to lose myself for an entire night in watching the steady flame of a lamp, |

| or the embers |

| of a fire; |

| to dream away whole days over the perfume of a flower; |

| to repeat |

| monotonously some common word, until the sound, by dint of frequent repetition, |

| ceased to convey any idea whatever to the mind; |

| to lose all sense of motion or |

| physical |

| existence, by means of absolute bodily quiescence long and obstinately |

| persevered in; |

| —such were a few of the most common and least pernicious vagaries induced by a |

| condition of the mental faculties, not, indeed, altogether unparalleled, |

| but certainly |

| bidding defiance to anything like analysis or explanation. |

| Yet let me not be misapprehended. |

| —The undue, earnest, and morbid attention thus |

| excited by objects in their own nature frivolous, must not be confounded in |

| character |

| with that ruminating propensity common to all mankind, and more especially |

| indulged |

| in by persons of ardent imagination. |

| It was not even, as might be at first |

| supposed, an |

| extreme condition or exaggeration of such propensity, but primarily and |

| essentially |

| distinct and different. |

| In the one instance, the dreamer, or enthusiast, |

| being interested |

| by an object usually not frivolous, imperceptibly loses sight of this object in |

| wilderness of deductions and suggestions issuing therefrom, until, |

| at the conclusion of |

| a day dream often replete with luxury, he finds the incitamentum or first cause |

| of his |

| musings entirely vanished and forgotten. |

| In my case the primary object was |

| invariably |

| frivolous, although assuming, through the medium of my distempered vision, a |

| refracted and unreal importance. |

| Few deductions, if any, were made; |

| and those few |

| pertinaciously returning in upon the original object as a centre. |

| The meditations were |

| never pleasurable; |

| and, at the termination of the reverie, the first cause, |

| so far from |

| being out of sight, had attained that supernaturally exaggerated interest which |

| was the |

| prevailing feature of the disease. |

| In a word, the powers of mind more |

| particularly |

| exercised were, with me, as I have said before, the attentive, and are, |

| with the daydreamer, |

| the speculative. |

| My books, at this epoch, if they did not actually serve to irritate the |

| disorder, partook, it |

| will be perceived, largely, in their imaginative and inconsequential nature, |

| of the |

| characteristic qualities of the disorder itself. |

| I well remember, among others, |

| the treatise |

| of the noble Italian Coelius Secundus Curio «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»; |

| St. |

| Austin’s great work, the «City of God»; |

| and Tertullian «de Carne Christi,» |

| in which the |

| paradoxical sentence «Mortuus est Dei filius; |

| credible est quia ineptum est: |

| et sepultus |

| resurrexit; |

| certum est quia impossibile est» occupied my undivided time, |

| for many |

| weeks of laborious and fruitless investigation. |

| Thus it will appear that, shaken from its balance only by trivial things, |

| my reason bore |

| resemblance to that ocean-crag spoken of by Ptolemy Hephestion, which steadily |

| resisting the attacks of human violence, and the fiercer fury of the waters and |

| the |

| winds, trembled only to the touch of the flower called Asphodel. |

| And although, to a careless thinker, it might appear a matter beyond doubt, |

| that the |

| alteration produced by her unhappy malady, in the moral condition of Berenice, |

| would |

| afford me many objects for the exercise of that intense and abnormal meditation |

| whose |

| nature I have been at some trouble in explaining, yet such was not in any |

| degree the |

| case. |

| In the lucid intervals of my infirmity, her calamity, indeed, |

| gave me pain, and, |

| taking deeply to heart that total wreck of her fair and gentle life, |

| I did not fall to ponder |

| frequently and bitterly upon the wonderworking means by which so strange a |

| revolution had been so suddenly brought to pass. |

| But these reflections partook |

| not of |

| the idiosyncrasy of my disease, and were such as would have occurred, |

| under similar |

| circumstances, to the ordinary mass of mankind. |

| True to its own character, |

| my disorder |

| revelled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the |

| physical frame |

| of Berenice —in the singular and most appalling distortion of her personal |

| identity. |

| During the brightest days of her unparalleled beauty, most surely I had never |

| loved |

| her. |

| In the strange anomaly of my existence, feelings with me, had never been |

| of the |

| heart, and my passions always were of the mind. |

| Through the gray of the early |

| morning —among the trellissed shadows of the forest at noonday —and in the |

| silence |

| of my library at night, she had flitted by my eyes, and I had seen her —not as |

| the living |

| and breathing Berenice, but as the Berenice of a dream —not as a being of the |

| earth, |

| earthy, but as the abstraction of such a being-not as a thing to admire, |

| but to analyze — |

| not as an object of love, but as the theme of the most abstruse although |

| desultory |

| speculation. |

| And now —now I shuddered in her presence, and grew pale at her |

| approach; |

| yet bitterly lamenting her fallen and desolate condition, |

| I called to mind that |

| she had loved me long, and, in an evil moment, I spoke to her of marriage. |

| And at length the period of our nuptials was approaching, when, upon an |

| afternoon in |

| the winter of the year, —one of those unseasonably warm, calm, and misty days |

| which |

| are the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon1, —I sat, (and sat, as I thought, alone, |

| ) in the |

| inner apartment of the library. |

| But uplifting my eyes I saw that Berenice stood |

| before |

| me. |

| - |

| Was it my own excited imagination —or the misty influence of the atmosphere —or |

| the |

| uncertain twilight of the chamber —or the gray draperies which fell around her |

| figure |

| —that caused in it so vacillating and indistinct an outline? |

| I could not tell. |

| She spoke no |

| word, I —not for worlds could I have uttered a syllable. |

| An icy chill ran |

| through my |

| frame; |

| a sense of insufferable anxiety oppressed me; |

| a consuming curiosity |

| pervaded |

| my soul; |

| and sinking back upon the chair, I remained for some time breathless |

| and |

| motionless, with my eyes riveted upon her person. |

| Alas! |

| its emaciation was |

| excessive, |

| and not one vestige of the former being, lurked in any single line of the |

| contour. |

| My |

| burning glances at length fell upon the face. |

| The forehead was high, and very pale, and singularly placid; |

| and the once jetty |

| hair fell |

| partially over it, and overshadowed the hollow temples with innumerable |

| ringlets now |

| of a vivid yellow, and Jarring discordantly, in their fantastic character, |

| with the |

| reigning melancholy of the countenance. |

| The eyes were lifeless, and lustreless, |

| and |

| seemingly pupil-less, and I shrank involuntarily from their glassy stare to the |

| contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips. |

| They parted; |

| and in a smile of |

| peculiar |

| meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my |

| view. |

| Would to God that I had never beheld them, or that, having done so, I had died! |

| 1 For as Jove, during the winter season, gives twice seven days of warmth, |

| men have |

| called this clement and temperate time the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon |

| —Simonides. |

| The shutting of a door disturbed me, and, looking up, I found that my cousin had |

| departed from the chamber. |

| But from the disordered chamber of my brain, had not, |

| alas! |

| departed, and would not be driven away, the white and ghastly spectrum of |

| the |

| teeth. |

| Not a speck on their surface —not a shade on their enamel —not an |

| indenture in |

| their edges —but what that period of her smile had sufficed to brand in upon my |

| memory. |

| I saw them now even more unequivocally than I beheld them then. |

| The teeth! |

| —the teeth! |

| —they were here, and there, and everywhere, and visibly and palpably |

| before me; |

| long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writhing |

| about them, |

| as in the very moment of their first terrible development. |

| Then came the full |

| fury of my |

| monomania, and I struggled in vain against its strange and irresistible |

| influence. |

| In the |

| multiplied objects of the external world I had no thoughts but for the teeth. |

| For these I |

| longed with a phrenzied desire. |

| All other matters and all different interests |

| became |

| absorbed in their single contemplation. |

| They —they alone were present to the |

| mental |

| eye, and they, in their sole individuality, became the essence of my mental |

| life. |

| I held |

| them in every light. |

| I turned them in every attitude. |

| I surveyed their |

| characteristics. |

| I |

| dwelt upon their peculiarities. |

| I pondered upon their conformation. |

| I mused upon the |

| alteration in their nature. |

| I shuddered as I assigned to them in imagination a |

| sensitive |

| and sentient power, and even when unassisted by the lips, a capability of moral |

| expression. |

| Of Mad’selle Salle it has been well said, «que tous ses pas etaient |

| des |

| sentiments,» and of Berenice I more seriously believed que toutes ses dents |

| etaient des |

| idees. |

| Des idees! |

| —ah here was the idiotic thought that destroyed me! |

| Des idees! |

| —ah |

| therefore it was that I coveted them so madly! |

| I felt that their possession |

| could alone |

| ever restore me to peace, in giving me back to reason. |

| And the evening closed in upon me thus-and then the darkness came, and tarried, |

| and |

| went —and the day again dawned —and the mists of a second night were now |

| gathering around —and still I sat motionless in that solitary room; |

| and still I sat buried |

| in meditation, and still the phantasma of the teeth maintained its terrible |

| ascendancy |

| as, with the most vivid hideous distinctness, it floated about amid the |

| changing lights |

| and shadows of the chamber. |

| At length there broke in upon my dreams a cry as of |

| horror and dismay; |

| and thereunto, after a pause, succeeded the sound of troubled |

| voices, intermingled with many low moanings of sorrow, or of pain. |

| I arose from my |

| seat and, throwing open one of the doors of the library, saw standing out in the |

| antechamber a servant maiden, all in tears, who told me that Berenice was —no |

| more. |

| She had been seized with epilepsy in the early morning, and now, |

| at the closing in of |

| the night, the grave was ready for its tenant, and all the preparations for the |

| burial |

| were completed. |

| I found myself sitting in the library, and again sitting there |

| alone. |

| It |

| seemed that I had newly awakened from a confused and exciting dream. |

| I knew that it |

| was now midnight, and I was well aware that since the setting of the sun |

| Berenice had |

| been interred. |

| But of that dreary period which intervened I had no positive —at |

| least |

| no definite comprehension. |

| Yet its memory was replete with horror —horror more |

| horrible from being vague, and terror more terrible from ambiguity. |

| It was a fearful |

| page in the record my existence, written all over with dim, and hideous, and |

| unintelligible recollections. |

| I strived to decypher them, but in vain; |

| while ever and |

| anon, like the spirit of a departed sound, the shrill and piercing shriek of a |

| female voice |

| seemed to be ringing in my ears. |

| I had done a deed —what was it? |

| I asked myself the |

| question aloud, and the whispering echoes of the chamber answered me, «what was |

| it?» |

| On the table beside me burned a lamp, and near it lay a little box. |

| It was of no |

| remarkable character, and I had seen it frequently before, for it was the |

| property of the |

| family physician; |

| but how came it there, upon my table, and why did I shudder in |

| regarding it? |

| These things were in no manner to be accounted for, and my eyes at |

| length dropped to the open pages of a book, and to a sentence underscored |

| therein. |

| The |

| words were the singular but simple ones of the poet Ebn Zaiat, «Dicebant mihi sodales |

| si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. |

| «Why then, as I |

| perused them, did the hairs of my head erect themselves on end, and the blood |

| of my |

| body become congealed within my veins? |

| There came a light tap at the library |

| door, |

| and pale as the tenant of a tomb, a menial entered upon tiptoe. |

| His looks were |

| wild |

| with terror, and he spoke to me in a voice tremulous, husky, and very low. |

| What said |

| he? |

| —some broken sentences I heard. |

| He told of a wild cry disturbing the |

| silence of the |

| night —of the gathering together of the household-of a search in the direction |

| of the |

| sound; |

| —and then his tones grew thrillingly distinct as he whispered me of a |

| violated |

| grave —of a disfigured body enshrouded, yet still breathing, still palpitating, |

| still alive! |

| He pointed to garments;-they were muddy and clotted with gore. |

| I spoke not, |

| and he |

| took me gently by the hand; |

| —it was indented with the impress of human nails. |

| He |

| directed my attention to some object against the wall; |

| —I looked at it for some |

| minutes; |

| —it was a spade. |

| With a shriek I bounded to the table, and grasped the box that |

| lay |

| upon it. |

| But I could not force it open; |

| and in my tremor it slipped from my |

| hands, and |

| fell heavily, and burst into pieces; |

| and from it, with a rattling sound, |

| there rolled out |

| some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with thirty-two small, |

| white and |

| ivory-looking substances that were scattered to and fro about the floor. |

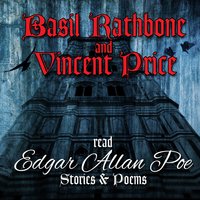

Lyrics Berenice - Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone

Song information On this page you can read the lyrics of the song Berenice , by -Vincent Price

In the genre:Саундтреки

Release date:14.08.2013

Select which language to translate into:

Write what you think about the lyrics!

Other songs by the artist:

| Name | Year |

|---|---|

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 |